Many people appreciate love, art, and even daydreaming, without realizing that they inherently make you stronger. While most people only think of evolution as a competitive tooth and nail fight to the top, in fact cooperation is also a strategy that evolved in this environment. People who share and cooperate with each other simply outcompete those who don’t.

Many people appreciate love, art, and even daydreaming, without realizing that they inherently make you stronger. While most people only think of evolution as a competitive tooth and nail fight to the top, in fact cooperation is also a strategy that evolved in this environment. People who share and cooperate with each other simply outcompete those who don’t.

This past summer, Scott Alexander posted a piece called Meditations on Moloch on his excellent blog, Star Slate Codex. I like this piece, since it is a strange mashup of ideas from Ginsberg’s Howl, AI disaster scenarios from Bostrum’s Superintelligence, and dark age ideas about how society should be structured from one of these new conservative types. This piece has really captured the imagination of the rationalist community and many people I know seem to fully agree with his viewpoint. I happen to disagree with some of the premises, so I want to clarify my thoughts on the matter.

… Scott Alexander posted a piece called Meditations on Moloch on his excellent blog, Star Slate Codex. I happen to disagree with some of the premises, so I want to clarify my thoughts on the matter.

It’s very hard to sum up Alexander’s post, as you might imagine from the disparate sources he is trying to bring together. But one key focus is on “multipolar traps,” in which competition causes us to trade away things we value in order to optimize for one specific goal. He gives many examples of multipolar traps, all of which are problematic for various reasons, but I will try to give one example that Bay Area home buyers can relate to: the two-income trap. Alexander believes that two-income couples are driving up home prices, and that if everyone agreed to have only one earner per household, home prices would naturally drop. Here is how Alexander sums up this particular multipolar trap:

It’s theorized that sufficiently intense competition for suburban houses in good school districts meant that people had to throw away lots of other values – time at home with their children, financial security – to optimize for house-buying-ability or else be consigned to the ghetto.

From a god’s-eye-view, if everyone agrees not to take on a second job to help win the competition for nice houses, then everyone will get exactly as nice a house as they did before, but only have to work one job. From within the system, absent a government literally willing to ban second jobs, everyone who doesn’t get one will be left behind.

So he is describing a sort of competition that helps no one, but that no one can escape from. It’s hard to think of how folks could coordinate to solve this, though a law capping real estate prices seems more realistic than banning second jobs. I actually think this is a bad example, since it seems to put the burden of driving up home prices on two-income families. In fact, I am confident that home prices demand two middle income earners because of the huge amount of capital amassed by the very rich. If all middle income earners coordinated their efforts and stopped buying homes priced above a certain level, I predict the crash in real estate prices wouldn’t last very long. The very rich would just continue snapping up real estate and drive the price right back up.

Alexander believes that two-income couples are driving up home prices, and that if everyone agreed to have only one earner per household, home prices would naturally drop. In fact, I am confident that home prices demand two middle income earners because of the huge amount of capital amassed by the very rich. If all middle income earners … stopped buying homes priced above a certain level … the very rich would just continue snapping up real estate and drive the price right back up.

Of course I’m happy to allow that multipolar traps do exist, government corruption is a persistent bane to civilization, for example. And Alexander himself points out that the universe has traits that protect humans from the destructive impact of multipolar traps. In his view, there are four reasons human values aren’t essentially destroyed by competition: 1. Excess resources, 2. Physical limitations, 3. Utility maximization, and 4. Coordination. Let me try to address each point in turn.

First, here is what Alexander says about excess resources:

This is … an age of excess carrying capacity, an age when we suddenly find ourselves with a thousand-mile head start on Malthus. As Hanson puts it, this is the dream time.

As long as resources aren’t scarce enough to lock us in a war of all against all, we can do silly non-optimal things – like art and music and philosophy and love – and not be outcompeted by merciless killing machines most of the time.

This actually seems like a misunderstanding of what resources actually are. Humans aren’t like reindeer on an island who die out after eating up all the food. Most animals are unable to manage the resources around them. (Though those other farming species ARE fascinating.) But for humans, resources are a function of raw materials and technology. Innovation is what drives increases in efficiency or even entirely new classes of resources (i.e. hunter and gatherers couldn’t make much use of petroleum). So in fact we are always widening the available resources.

I don’t believe we are in some Dream Time, when humans have a strange abundance of resources, and that we are doomed to grow our population until we reach a miserable Malthusian equilibrium. It’s well understood that human fertility goes down in advanced (rich) cultures and is more highly correlated with female education than food production. Humans seem to be pretty good about reigning in their population once they are educated and healthy enough. There is some concern about fertility cults like Mormons and Hutterites, but time isn’t kind to strange cults. Alexander himself points out that their defection rates are very high. It’s not fun taking care of so many kids, I hear.

I don’t believe we are in some Dream Time, when humans have a strange abundance of resources, and that we are doomed to grow our population until we reach a miserable Malthusian equilibrium. It’s well understood that human fertility goes down in advanced (rich) cultures and is more highly correlated with female education than food production. … Actually, innovation might just be a function of population, so the more people we have, the more innovation we will have. Innovation (and conservation) will always expand the resources available to us.

But actually, innovation might just be a function of population, so the more people we have, the more innovation we will have. Innovation (and conservation) will always expand the resources available to us. It’s foolish to think that we have learned all there is to know about manipulating matter and energy or that we will somehow stop the trend of waste reduction.

But a more interesting point to consider is that art, music, philosophy, and love actually make cultures MORE competitive. The battlefield of evolution is littered with “merciless killing machines” who have been conquered by playful, innovative humans. This has been my most surprising insight as I examined my objections to Alexander’s Moloch or Hanson’s Dream Time. In fact, it’s the cultures with art, philosophy, and love that have utterly crushed and destroyed their competitors. And the reason is complex and hard to see. Surely art and love are facilitators of cooperation, which allows groups to cohere around shared narratives and shared identities. But Hanson and Alexander are dismissing these as frivolous when they actually form the basis of supremacy. Even unstructured play is probably essential to this process of innovation that allows some cultures to dominate. Madeline Levine has a lot to say about this.

Alexander alludes to this poem by Zack Davis that imagines a future world of such stiff competition that no one can indulge in even momentary daydreaming. … But a more interesting point to consider is that art, music, philosophy, and love actually make cultures MORE competitive. … In fact it’s (these) cultures that have utterly crushed and destroyed their competitors.

Alexander alludes to this poem by Zack Davis that imagines a future world of such stiff competition that no one can indulge in even momentary daydreaming. But this is a deeply flawed understanding of innovation. Innovation is about connecting ideas, and agents that aren’t allowed to explore idea space won’t be able to innovate. So daydreaming is probably essential to creativity. In rationalist terms, Davis imagines a world in which over-fitted hill climbers will dominate, when in fact, they will all only reach local maxima, just as they always have done. They will be outcompeted by agents who can break out of the local maxima. It’s especially ironic that he uses contract drafting as an example where each side has an incentive to scour ideaspace for advantageous provisions that will still be amenable to the counterparty.

It’s strikes me as very odd to think that human values are somehow at odds with natural forces. Alexander brings up how horrible it is that a wasp would lay its eggs inside a caterpillar so that it’s young could hatch and consume from the inside out. Yet, humans lovingly spoon beef baby food into their toddler’s mouths that is derived from factory farm feedlots, which are so filthy that some cows fall over and can no longer walk, but are just bulldozed up into the meat grinder anyway. So much for tender human sensibilities. This might be a good example of where sociopaths can play a role in the population dynamics. A few psycho factory farmers can provide food for the vast squeamish billions who lack the stomach for such slaughter.

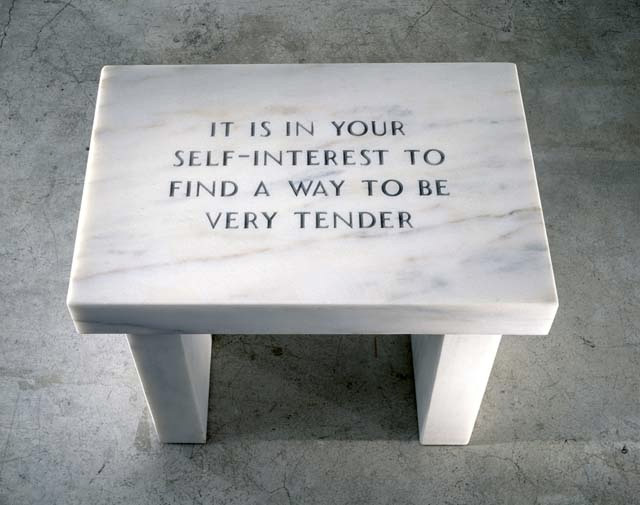

Because really, love conquers all, literally. Alexander overlooks this:

But the current rulers of the universe – call them what you want, Moloch, Gnon, Azathoth, whatever – want us dead, and with us everything we value. Art, science, love, philosophy, consciousness itself, the entire bundle. And since I’m not down with that plan, I think defeating them and taking their place is a pretty high priority.

In fact, the universe has been putting coordination problems in front of living organisms for billions of years. Multicellular organisms overcame the competition between single cells, social animals herded together to survive, and humans harnessed art, science, philosophy, and maybe even consciousness, to take cooperation to a whole other level. Far from being a strange weak anomaly, cooperation in all its forms is the tried and true strategy of evolutionary survivors. Alexander makes an allusion to this at the end of his essay when he mentions Elua:

Elua. He is the god of flowers and free love and all soft and fragile things. Of art and science and philosophy and love. Of niceness, community, and civilization. He is a god of humans.

The other gods sit on their dark thrones and think “Ha ha, a god who doesn’t even control any hell-monsters or command his worshippers to become killing machines. What a weakling! This is going to be so easy!”

But somehow Elua is still here. No one knows exactly how. And the gods who oppose Him tend to find Themselves meeting with a surprising number of unfortunate accidents.

No one is sure how Elua survives? Well, it’s clear that multicellular organisms outcompete single-celled organisms. The cooperative armies of the early civilizations defeated whatever hunter gatherer tribes they came across. The nonviolent resistance of India ended British rule, and the Civil Rights movement in America mirrored that success. Modern America has drawn millions of immigrants in part due to its arts and culture, which are known around the world. Coordination is a powerful strategy. Love, art, and culture are all tools of coordination. They are also probably tools of innovation. If creativity is drawing connections between previously unconnected concepts, then having a broader palette of concepts to choose from is an obvious advantage.

Love, art, and culture are all tools of coordination. They are also probably tools of innovation. If creativity is drawing connections between previously unconnected concepts, then having a broader palette of concepts to choose from is an obvious advantage.

Cooperation has certainly evolved, and so have human values. I am with Pinker on this. Alexander prefers to quote esoteric texts in which time flows downhill. But in Pinker’s world, we are evolving upward. Why not? Life is some strange entropy ratchet after all, why not just go with it. But if our values are tools that have evolved and are evolving, then it doesn’t make sense to lock them in place and jealously protect them.

Alexander is a good transhumanist, so he literally wants humanity to build a god-like Artificial Intelligence which will forever enshrine our noble human virtues and protect us against any alternative bad AI gods. I can’t really swallow this proposition of recursively self-improving AI. My most mundane objection is that all software has bugs and bugs are the result of unexpected input, so it seems impossible to build software that will become godlike without crashing. A deeper argument might be that intelligence is a network effect that occurs between embodied, embedded agents, which are tightly coupled to their environment, and this whole hairy mess isn’t amenable to instantaneous ascension.

But I will set aside my minor objections because this idea of fixed goals is very beloved in the rationalist scene. God forbid that anyone mess with our precious utility functions. Yet, this seems like a toy model of goals. Goals are something that animals have which are derived from our biological imperatives. For most animals, the goals are fairly fixed, but humans have a biological imperative to sociability. So our goals, and indeed our very desires, are subject to influence from others. And, as we can see from history, human goals are becoming more refined. We no longer indulge in cat burning, for example. This even happens on the scale of the individual, as young children put aside candy and toys and take up alcohol and jobs. An AI with fixed goals would be stunted in some important ways. It would be unable to refine its goals based on new understandings of the universe. It would actually be at a disadvantage to agents that are able to update their goals

If we simply extrapolate from historical evolution, we can imagine a world in which humans themselves are subsumed into a superorganism in the same way that single-celled organisms joined together to form multicellular organisms. Humans are already superintelligences compared to bacteria, and yet we rely on bacteria for our survival. The idea that a superintelligent AI would be able to use nano-replicators to take over the galaxy seems to overlook the fact that DNA has been building nano-replicators to do exactly that for billions of years. Any new contestants to the field are entering a pretty tough neighborhood.

So my big takeaway from this whole train of thought is that, surprisingly, love and cooperation are the strategies of conquerors. Daydreamers are the masters of innovation. These are the things I can put into effect in my everyday life.

So my big takeaway from this whole train of thought is that, surprisingly, love and cooperation are the strategies of conquerors. Daydreamers are the masters of innovation. These are the things I can put into effect in my everyday life. I want to take more time to play and daydream to find the solutions to my problems. I want to love more and cooperate more. I want to read more novels and indulge in more art. Because, of course, this is the only way that I will be able to crush the competition.