I often feel that the hardest problems of the future are political. The most obvious example of this is the green revolution. I love to think about how the Haber process allowed humans to pull nitrogen from the air and create fertilizer. It’s estimated that 40% of humans alive today owe their existence to this process. Yet, we clearly haven’t eliminated world hunger. We haven’t even eliminated hunger here in the USA. Bright eyed positivists may insist that we merely need the next big breakthrough to make food even cheaper. Ray Kurzweil rightly points out that many revolutionary technologies start out expensive and faulty, only to end up cheap, reliable, and ubiquitous through exponential progress. The worldwide explosion of mobile technology is a recent example of this.

I often feel that the hardest problems of the future are political. The most obvious example of this is the green revolution. I love to think about how the Haber process allowed humans to pull nitrogen from the air and create fertilizer. It’s estimated that 40% of humans alive today owe their existence to this process. Yet, we clearly haven’t eliminated world hunger. We haven’t even eliminated hunger here in the USA. Bright eyed positivists may insist that we merely need the next big breakthrough to make food even cheaper. Ray Kurzweil rightly points out that many revolutionary technologies start out expensive and faulty, only to end up cheap, reliable, and ubiquitous through exponential progress. The worldwide explosion of mobile technology is a recent example of this.

But I remain unconvinced that we can rely on technology alone to improve the human condition. Our world will not spontaneously transform into the Star Trek world that Gene Roddenberry envisioned, in which humanity, freed from the need to toil for base survival, casts money aside and boldly strides among the stars. Americans in particular seem highly averse to this scifi socialism, as I have noted before. Perhaps we are too ruggedly independent, valuing personal accountability and self-reliance over care for the poor and needy.

Yet, as wealth inequality increases along with automation, the Lights in the Tunnel scenario outlined by Martin Ford becomes more likely. Ford argues that the Luddite Fallacy, which shows that automation creates jobs in other sectors, will soon come to an end as humans fall further and further behind machine capabilities. If fewer people can work, then fewer people will be able to purchase goods. The law of diminishing propensity to consume dictates that the economy will thus contract with fewer consumers. After all, by the time you have purchased your fifth super-yacht, they start to become boring.

Marshall Brain offers a wonderful market based solution to this problem: give everyone a $25,000 per year stipend. They will spend this money as they see fit, allowing the markets to continue functioning as consumers pick the winning and losing companies based on how well these companies meet consumer preferences. As Vernor Vinge says, humans excel at one thing that machines can’t yet compete with: we want things. But this is simply a non-starter politically here in the USA. Especially with the Tea Party types screaming for less government and more personal accountability, and frankly, not even the liberals are putting forth this radical of an idea.

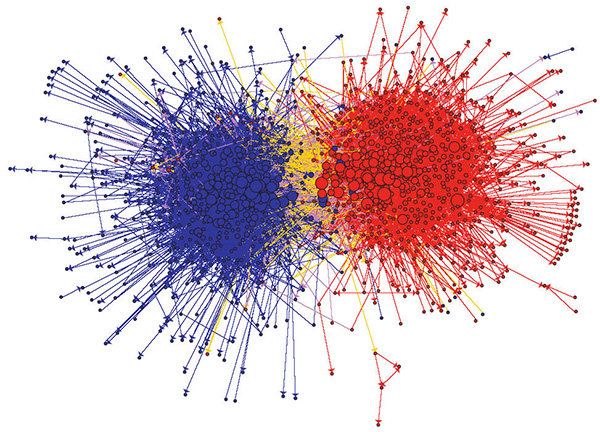

This graph of the liberal and conservative blogosphere sums up the problem nicely:

This is a bit old, but it shows the links between conservative and liberal blogs back in 2004. Note that few blogs are in the middle and there are few links between the two clusters. This is referred to as selective exposure. We all naturally seek out ideas that we agree with. But it makes it hard to communicate with the other side if you are just indignantly preaching to the choir with spittle flying from your lips. And the spittle doth fly. With Congress in gridlock, the media pundits on both sides spew vitriol at the other, and it sometimes feels as though there are two Americas (At least two really).

This is where Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations theory comes to the rescue.* Haidt factored human values into five major foundations with a tentative sixth:

THE MORAL FOUNDATIONS

1) Care/harm: … Related to our long evolution as mammals with attachment systems and an ability to feel (and dislike) the pain of others. It underlies the virtues of kindness, gentleness, and nurturance.

2) Fairness/cheating: … Ideas of justice, rights, and autonomy. [Note: In our original conception, fairness included concerns about equality, which are more strongly endorsed by political liberals. However, as we reformulated the theory in 2011 based on new data, we emphasize proportionality, which is endorsed by everyone, but is more strongly endorsed by conservatives.]

3) Loyalty/betrayal: … Related to our long history as tribal creatures able to form shifting coalitions. It underlies the virtues of patriotism and self-sacrifice for the group. It is active any time people feel that it’s “one for all, and all for one.”

4) Authority/subversion: … Shaped by our long primate history of hierarchical social interactions. It underlies virtues of leadership and followership, including deference to legitimate authority and respect for traditions.

5) Sanctity/degradation: … Shaped by the psychology of disgust and contamination. It underlies religious notions of striving to live in an elevated, less carnal, more noble way. It underlies the widespread idea that the body is a temple which can be desecrated by immoral activities and contaminants (an idea not unique to religious traditions).

We think there are several other very good candidates for “foundationhood,” especially:

6) Liberty/oppression: This foundation is about the feelings of reactance and resentment people feel toward those who dominate them and restrict their liberty. Its intuitions are often in tension with those of the authority foundation. The hatred of bullies and dominators motivates people to come together, in solidarity, to oppose or take down the oppressor. We report some preliminary work on this potential foundation in this paper, on the psychology of libertarianism and liberty.

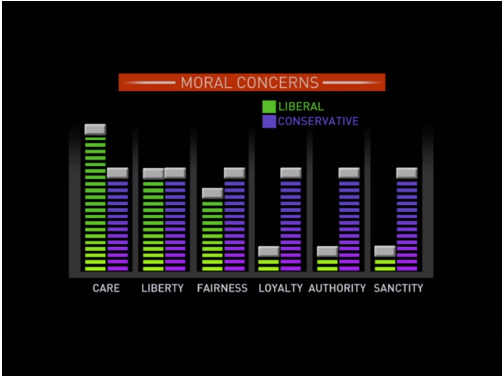

This picture sums up the idea nicely:

Here we see how much liberals (green) and conservatives (purple) value each of the moral foundations. Notice that conservatives value all of the foundations more or less equally, while liberals value care, liberty, and fairness, but disdain loyalty, authority, and sanctity. Hmm, sounds about right to me. I considered myself a liberal for a long time, and I have a hard time seeing the sense in valuing authority for its own sake. But along the way, I have met a bunch of earnest, intelligent, conservatives and libertarians, who seem to sincerely believe that their ideology will result in the best outcomes for everyone. And I have a hard time demonizing the conservative I share coffee with as we discuss the singularity.

What I love about the Moral Foundations Theory is that it offers us a key to bridge the divide between these two Americas, liberal and conservative. (Libertarians are different and value the liberty dimension above all others, apparently.) When viewed through the lens of moral foundations, some conservative positions become much more intelligible, especially when considering the three great differentiators: loyalty, authority, and sanctity.

Take illegal immigration for example. Liberals tend to be soft on this issue and more welcoming of immigrants in general. The conservative position might seem cold hearted and provincial. All rational arguments about the economic benefits of immigration (i.e. leads to greater GDP) fall on deaf ears. Even the fairness argument that we were all immigrants once (except indigenous people) fails to gain much traction with staunch conservatives. But instead of throwing up their hands and deciding that conservatives are simply evil, liberals might do well to pause a moment and consider how illegal immigration could undermine our democracy.

The formal immigration process tries to ensure that immigrants are familiar with the institutions of the United States. In order to become citizens, they must learn about our constitution, history, and democratic values. This helps them understand how democracy is SUPPOSED to work. The countries many immigrants come from don’t have good American things like rule of law or freedom of speech. If they become citizens illegally, it’s not clear that they will understand how to fight for democratic values. This will result in a growing underclass, afraid to speak up for themselves, woefully unaware of enlightenment era concepts of individual rights. The formal immigration process also teaches immigrants the story of America, which creates a coherent American narrative that will help us relate to each other and move forward as a people. This is just one example of how carefully considering a conservatives’ moral foundations reveals nuances to our nation’s problems, and hopefully could reveal a path towards compromise.

The 4th of July is something of an ambiguous holiday for liberals, and really liberals probably are a bit deficient in patriotism, or loyalty to our country. They don’t seem to value this moral foundation of loyalty much. And that is a shame really. I heard Danielle Allen, author of a new book on the Declaration of Independence, on NPR today, and was struck again at the visionary struggle that the founders of our nation underwent as they carefully crafted America’s seminal texts. I personally will take Allen’s advice and read the declaration in its entirety. Because for all its flaws, I am proud of this American experiment. Sure, we are no Scandinavia with its admirable socialism. But the Scandinavians can’t match our pluralism. Not to mention the fact that when’s the last time a cool band came out of there? Abba?

America actually is the coolest country in the world. And as I feel a stirring of patriotism on this holiday, I think that I am becoming a reformed liberal. One who might value loyalty a little bit after all. One who might reach out to my conservative friends and try to pry the rules of tradition** from their hands, while offering some good rational alternatives in exchange, which satisfy their moral sensibilities. Because America is awesome, and if we don’t all get together and craft a solution, it will all go to hell when the robots take over.

* Err, I know, the corruption thing needs to get worked out first.

** This conservatives-slavish-hue-to-heuristics idea is worth further examination.

[UPDATE 10/17/2015]

I like ideas like Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory because it seeks to establish some first principles from which we should be to extrapolate why the left and the right disagree in our country. Same for Muder’s inherited obligations of conservatives vs negotiated obligations of liberals. But then I went on Facebook and tried to use these principals to actually argue with a conservative and I failed utterly. I was trying to understand by what principle do conservatives oppose abortion which kills babies but support wars that kill babies. The answer I got was that morals don’t need to be consistent. We can have one justification for a certain position and an entirely different justification for another. But the problem is that this sounds irrational to me. I want human morals to be ultimately rational, but I should know better.

I do believe that morals are adaptive. We adopt the morals of the tribe around us so that they won’t kill us (in uncooperative environments) or so that we can flourish (in more cooperative environments) Robin Hanson would probably point out that these morals are just social signalling to help us identify with our in groups. There is no more rhyme nor reason to the pattern of beliefs held by liberals or conservatives any more than the spots of a peacock feather.