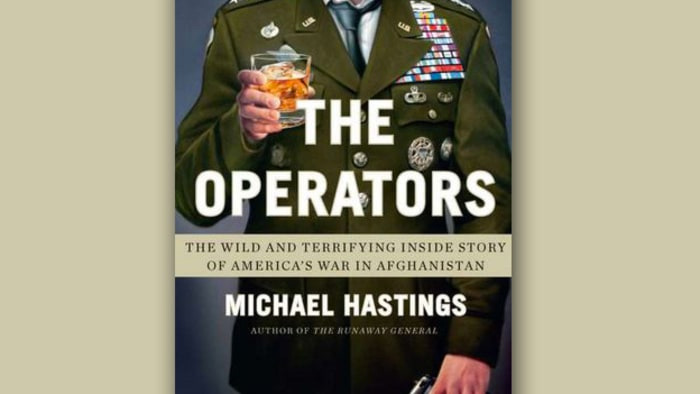

The Operators, by Michael Hastings

The Operators, by Michael Hastings

I went to a poetry reading in North Beach last week and then out drinking with the poets and their friends afterwards. This fulfilled an old Beatnik fantasy of mine. As I teenager, I venerated the Beat generation writers like Kerouac and Ginsberg. Their jazz-fueled, drug-laden epiphanies, wandering barefoot through the city at dawn, seemed a far cry from my suburban ennui, where the shopping mall was the hottest spot for us teens to gather. But there I was, last week, sitting in an old North Beach bar, arguing about Hemingway with a bunch of old hippie communist poets in the very place that Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Cassady might have had the same disagreement. It was like a dream come true.

Communists that they are, these poets blamed all of modernism’s ills on capitalism exclusively, it’s all about the money for them. Marx himself was a modernist in my own view, and the systems inspired by his visions have fared no better than those driven by capital in terms of real human flourishing, but I’m grinding a different axe today. See, the commies are convinced that it’s all about the money. Why has the US been venturing into the Middle East for so many years, wasting money and lives, as we clumsily sow chaos throughout the region? It must be for the money. “No Blood For Oil” read the protest signs. And it’s not an exclusively leftist position to take. Eisenhower himself coined the phrase “military-industrial complex” to warn of these powerful vested interests, and he was technically a Republican, though no Republican today would tolerate his views, I’m sure.

I hate to say this, postmodernist that I am, but there’s a part of me that thinks, if the US needs oil, it will grab oil. Our country is a system, competing with other systems for resources. I’d rather live under our system than under the Chinese or Russians, so I grit my teeth and bear it. But if you look at the details of the Iraq war, for example, huge Iraqi oil fields were ruined with water when they were disrupted by the war. Maybe some US oil companies benefitted temporarily from transient spikes in oil prices, but it’s not like the US is literally pumping the oil and taking it away. The US isn’t really benefitting from Iraqi oil. We spent way, way more on that war than we got back in free oil. One might say, well, it’s these multinational oil corporations that benefited. But it’s not at all clear why multinationals would care which regime they got their oil from. Saddam Hussein couldn’t pump the stuff himself.

And then there’s this whole line of reasoning that Hussein was threatening the US petrodollar by accepting euros for oil. And that seems like a decent argument, and would actually be aligned with US interests. Sure, we want the dollar to be propped up by the fact that it’s a global reserve currency. That’s fine, in a sense. Like it or hate it, if the purpose of the military-industrial complex is to preserve western dominance, as Chomsky might say, then this is just the sort of thing we should EXPECT it to do, and crying about it isn’t going to change the realpolitik of the situation. Powerful systems crush weak systems, end of story.

But then I ask myself, what if these systems AREN’T functioning to preserve US dominance? It may well be that US interests have actually been harmed by our Middle East adventures. We’ve certainly spilled plenty of blood and cash in Afghanistan for no apparent benefit. No oil there. Some pipeline theories float around, or maybe there’s a huge cache of rare earth metals we can grab, but, based on our track record, the US will probably fail to profit from either rare earth metals or pipelines.

It doesn’t seem like our military-industrial complex is being guided by the principle of advancing US interests. And that’s actually a bigger problem than if it were. If we were just bullies stomping on weak nations to make ourselves stronger, that wouldn’t be so bad, really. . . But if the military-industrial complex ISN’T guided by principles . . . if it fails to advance US interests, then it could destroy the US.

It doesn’t seem like our military-industrial complex is being guided by the principle of advancing US interests. And that’s actually a bigger problem than if it were. If we were just bullies stomping on weak nations to make ourselves stronger, that wouldn’t be so bad, really. As Pinker asserts in Better Angels, we have a long history in the West of becoming more and more civilized. If we’re bullies, we can learn to be gentle. But if the military-industrial complex ISN’T guided by principles, then it runs the risk of killing the goose that laid the golden egg. If it fails to advance US interests, then it could destroy the US, and there could be no more US to suck money out of at some point.

We saw a similar thing play out with the bank bailouts. A proper capitalism with accountability for making bad bets removes stupid strategies from the marketplace and should sustainably generate wealth for many. A crony capitalism that offloads risk onto the taxpayers threatens to break the very system from which its wealth is built.

What if these systems that we depend upon are broken? What if we didn’t go to war with Iraq to get the oil, we just went to fulfill the contracts of the military contractors? That just seems so crazy. Surely there should be someone at the wheel, guiding this whole thing, who would see a problem with that? But maybe not.

I read The Operators, by Michael Hastings. . . The big takeaway for me was that the military seems to be driven by a cult of bloodlust. . . The officers aren’t fighting for their country, they’re fighting to spill blood and to risk their own troop’s blood, in and of itself. . . Hastings describes war as a drug, the ultimate adrenaline high. And that paints an ugly picture. The actual foot soldiers think they’re fighting for their country, but they’re actually fighting out of loyalty to their fellow soldiers. The Pentagon starts a war simply to deploy assets and make sure that the defense industry gets paid, and the officers execute it because spilling blood is such a fucking RUSH, man! Holy shit, we’re fucked. . . This is a terrible system.

I had sort of accepted that defense contract spending was driving US military intervention, but then I read The Operators, by Michael Hastings. There’s a lot to say about this excellent book and its unfortunate author, but the big takeaway for me was that the military seems to be driven by a cult of bloodlust. On some level, the officers aren’t fighting for their country, they’re fighting to spill blood and to risk their own troop’s blood, in and of itself. It’s not even clear if they see these war theaters as proving grounds for their character, which would have some virtue, I guess. Hastings describes war as a drug, the ultimate adrenaline high. And that paints an ugly picture. The actual foot soldiers think they’re fighting for their country, but they’re actually fighting out of loyalty to their fellow soldiers. The Pentagon starts a war simply to deploy assets and make sure that the defense industry gets paid, and the officers execute it because spilling blood is such a fucking RUSH, man! Holy shit, we’re fucked. The wheels cannot help but come off of this system. Maybe we don’t have to outrun the bear, maybe we just need to outrun the other guys running from the bear, but come on. This is a terrible system.

To my conservative friends, my pals who defend modernism and think that it’s us postmodernists who have dismantled the system: Take a closer look at our systems. We postmodernists are doing you a favor by pointing out the flaws. We haven’t come up with any sustainable solutions, granted, but we didn’t CREATE these flaws. And now it seems to be up to ALL of us, modernists, traditionalists, postmodernists, whatever, to figure out a post-postmodernism that builds sustainable systems guided by principles and not just lust for cash and blood. God help us.