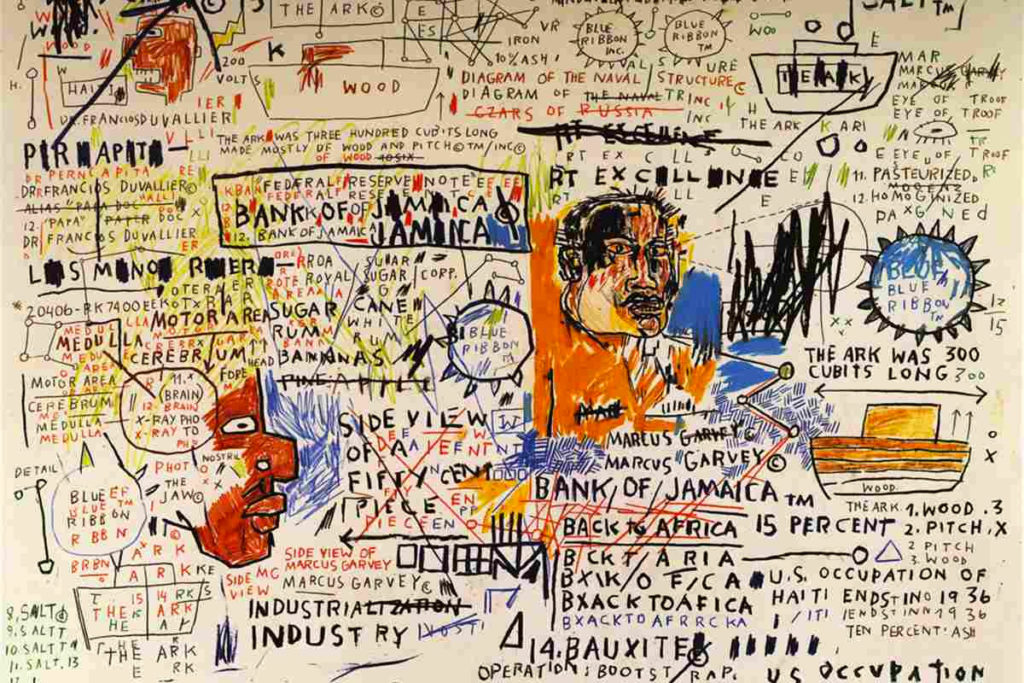

50 Cent Piece, by Jean-Michel Basquiat

50 Cent Piece, by Jean-Michel Basquiat

We generally think of art as beautiful, but perhaps nonessential. Or it’s essential for the soul, if you go for that sort of thing. “Man does not live by bread alone,” and so forth. But we don’t think of it as essential for survival. At a meetup the other day, an artist even told me that they thought art served needs fairly high on Maslow’s Hierarchy. But, you know, there is evolution and natural selection. And selection pressure doesn’t allow maladaptive traits to hang on. Why haven’t the fools who waste time and energy on art been outcompeted and removed from the gene pool by wiser, soulless working machines? It’s a conundrum, it is.

Go ask our venerable futurist thought leader, Robin Hanson, and he will tell you, oh well, this is the Dreamtime, don’t you know? This rich, industrialized era is an aberration and we will soon return to the Malthusian equilibrium that has dominated all human and animal life throughout time. Malthus envisions us as stupid animals, reproducing until we’ve eaten every spare scrap of food around us and are forced into abject misery. I get chafed at the very mention of Malthus and his empirically bereft theories, but that’s a battle for another day. I find it generally makes sense to listen carefully to Hanson, and I try to understand what he has to say.

But then Scott Alexander, the bard of the rationalists, came out with his Moloch piece a few years ago, and shaped an entire narrative incorporating these Malthusian and Hansonian ideas, and really it was just too much for me. He is a great writer, this Alexander, and the rationalists all around me consumed his narrative with relish, experiencing not the slightest indigestion. I was left to gnash my teeth quietly off in the hinterlands of Oakland, wrestling with my intuition. I tasted of this Moloch soup, but I could not keep it down.

How can art be a maladaptive thing? Evolution doesn’t allow maladaptive traits to persist in populations. Even if it’s only a very small handicap, evolution will remove a trait over time. But there are periods of relaxed selection, and these correspond to explosions of diversity. Weeds will grow while the gardener sleeps. So perhaps that explains it. Oh, sad story. That thing you value, that song that compels you to dance, that dance you do in spastic ecstasy, are all for naught. The gardener will soon awaken and trim such foolishness away. Selective pressure will increase once again, and all of us who wasted effort dancing will end up in the soup pots of those who didn’t squander their fitness on such frivolity.

And if we look at the world in a certain way, it looks like it’s filled with maladaptive behavior. Surely this is a time of superstimuli and dysgenic birth control and porn. The wise look sadly on and see relaxed selection at work. Tisk, tisk, such a pity. But, you know, a proper skeptic kicks the tires of his own conceptual framework now and then, and, hark, what is this we find? A crack in the narrative? Do you know what looks a lot like relaxed selection? I will tell you, it’s positive adaptation. How confident can we be that we actually know what’s adaptive and what isn’t? Surely having the most children possible is the most adaptive strategy, yes? Then how did we end up with various parental investment strategies? (Some people having lots of kids and giving them only a little attention, and some people having only a few kids and giving them lots of attention.) Hmm. Wait a minute! Maybe even frivolous art is a POSITIVE adaptation. Not a thing to feed the soul, but a thing to feed the belly.

Some people think that the only way that art could be adaptive is if it helped an artist personally by making them more attractive to mates or allowing them to trade art for food. But let’s look at very early human art, such as the drawings cavemen made when they were going to hunt large prey. These drawing might have been hunting plans. And, in that case, the tribes who made these drawings (art) would outcompete those that didn’t. And yes, like the biologist E.O. Wilson, I believe that there is such a thing as groups outcompeting other groups.

Art has beauty that draws us to it and this connects us as tribes. When we dance together, we form bonds. And this was as true around paleolithic campfires as it is today at Gilman Street punk rock shows. So here I will present to you some mechanisms by which art may be a positive adaptation.

1) Art Speaks the Language of the Subconscious

A few years ago, I went to a rationality workshop put on by CFAR. At this workshop, there was much talk of Kahneman’s model of two major ways in which the mind works. System 1 roughly corresponds to the subconscious or the preconscious mind, and is the realm of fast, effortless thinking, intuition, and emotions. System 2 is conscious thought and is slow and effortful and where we expect logic and planning to occur. Surprisingly to me, CFAR seemed more concerned with System 1 than with System 2. System 1 seems to be where motivation comes from. So a lot of effort was devoted to getting System 1 to align with System 2 goals, so that you actually feel motivated to do things today which have payoffs far in the future.

What the hell does this have to do with art being adaptive? I’m glad you asked. See, the instructors at CFAR think one way of getting messages into System 1 is to use very exaggerated and sense-based imagery. So if you want to remember to check the mail when you get home, perhaps you should picture a massively distorted mailbox and imagine the crisp scent of paper. Isn’t it interesting how much art has these same properties? Novels contain a lot of exaggerated language about sensory experiences and vocals contain exaggerated emotion. It may be that art is memorable to the degree that it takes advantage of this exaggerated, System 1 communication. And it is a unique channel in this regard. Scientific or mathematical writing is fairly bereft of this.

2) Art Populates the Database of Experience with Novel Patterns

Another interesting CFAR exercise was CoZE (Comfort Zone Expansion). The goal was to get everyone to try new things and gain new experiences. System 1 functions as a pattern matcher, and populating your subconscious with more patterns will make it more powerful. So you can go and try new things all the time, which is hard. OR you can go and virtually gain new experience by reading stories, listening to songs, or looking at crazy paintings and sculptures. And who knows what use these strange patterns will end up serving? Musk disdains such metaphorical thinking, but see how much technology mimics the things we observe in nature. Bell’s telephone was inspired by the workings of the inner ear, and deep learning is patterned after the neural networks of our own brains.

Perhaps reading about how a love affair goes awry in Shakespeare will inform our own love lives. In The Better Angels of Our Nature, Pinker suggests that one mechanism of our evolving morality might be literature and the arts, which gives us insights into the minds of others. Or, stranger yet, perhaps we will hear some weird pattern in a song that inspires us to create a new technology that no one has imagined yet.

3) Art Reduces Communication Costs

Aside from the raw potential of art to populate our subconscious with patterns and inspire us, art often serves as a substrate for coordination. Entire subcultures have arisen around shared admiration for music or comic books. How does art facilitate this coordination at punk rock shows or cosplay conventions? One mechanism is the reduction of communication costs. Art provides narratives that allow people to situation themselves within. Punk rock is an expression of postmodern dissatisfaction with the fakery of conformist, consumer culture. Punks don’t need to explain all of this to one another (although they certainly delight in doing so) because they can refer to a single song to express an entire range of ideas.

Eliezer Yudkowsky has used art to good effect to coordinate an entire subculture of rationalists around his HPMOR fan fiction. I haven’t read it myself, but I don’t know how many times I’ve heard a rationalist refer to Quirrel and have seen the others in the group nod sagely. If only I had read HPMOR, I could have gotten the point. Entire modes of approaching problems can be summed up in a single fictional character.

We even see narratives at work coordinating corporate culture. Peter Thiel is famous for this, naming his companies after artifacts from Tolkien’s world. Palantir is a seeing stone in Tolkien’s fiction, created for good, but turned to evil. Palantir, the company, offers analytic software to the government and perhaps Thiel wants to warn his people to heed the cautionary tale that Tolkien intended. Mithril Capital references Tolkien’s precious metal, which has a beauty that never tarnishes or grows dim. Not hard to see what sort of investments they would be seeking.

Of course every field has shared jargon that compacts a lot of bigger ideas and serves the purpose of reducing communication costs. But the beauty of art is that its metaphorical nature makes this jargon more generalizable, allowing it to cut across disciplines.

4) Art Appreciation Demonstrates Shared Values

Art has also served as a way to demonstrate shared values. See how closely art was tied to the church in the Middle Ages. Or how gospel songs bound together the protesters of the Civil Rights Movement. It seems a shame that modern artists aren’t providing the Black Lives Matter movement with more compelling art to disarm their right wing opponents. And of course this is true in subcultures as well. Fellow goths know that darkness lives in your soul when you display your Joy Division t-shirt.

So art really has all sorts of traits that make it seem like a positive adaptation, not just a maladaptive trait that survives due to weak selection pressure. So what? Well, I know that I have neglected art in my own life recently, and this thesis makes me see it in a new light. Art isn’t merely a pleasant diversion. Art appreciation binds us to others in our tribe and populates our subconscious with powerful experiences. It serves as a substrate for coordination that sinks deeply into our souls (err, System 1’s) and can inspire and motivate us like no mere mission statement. So we should take up art, not only for its beauty, but also with a proper concern for our own self-interest. Art is a powerful superweapon. Take that, Moloch.

Art is adaptive, but only art of a certain sort.

Namely, it (1) teaches useful things, and/or (2) inspires and unites the people.

Cave paintings and the Venus figurines (if the theories that they represented the various stages of pregnancy are correct) are an excellent example – and as it just so happens, probably the first one – of the former. The great literary classics serve this function; many of them can be viewed as self-help guides to functioning in a complex society.

As for inspiration/unification, this includes epic literature (The Illiad and The Odyssey being the foundational palimsest for the Western tradition); the religious texts that unified the great empires during the Axial revolution; and a huge percentage of European musical and visual artistic output from 1500-1900 (the “nationalist” theme that came to the fore in the 19th century – in music, represented by Wagner, Verdi, Mussorgsky, Dvorak, Brahms, Chopin, even Vaughan Williams in Britain – is the clearest illustration of this).

Then postmodernism started creeping in at the turn of the century with the likes of Stravinsky and Kandinsky, then you had the Frankfurt school, crazy French philosophers, “critical theory,” the CIA helping the whole thing alone (fact not a conspiracy theory). As a result, we have now descended into an aesthetic hell, of which the opus at the top of this post is quite the apt example of.

What is known as “modern art” has severed its connection to life, and as such, it has divorced itself from both truth and beauty.

Why?

I would argue that this is a luxury made affordable by precise virtue of us living in the Hansonian dreamtime. In art as in life more general we have become divorced from the struggle for survival, both personally and as nations. This has massively relaxed selection in the arts and directly enabled postmodernism. (The exception proves the rule: The only country that continues to churn out heroic paintings, military marches, etc. en masse and at a state-sanctioned level is North Korea).

Anyone in the West who would devote his life to patriotically-themed painting ala Jacques-Louis David, John Gast, or Vasnetsov today would be dismissed as a crank living in… well, the 19th century. It’s cooler today to randomly splatter paint on a canvass and (if you belong to the appropriate clique) sell it to an art speculator, who will in turn sell it on to some billionaire or hedge fund.

Here is a quote from Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being that illustrates this:

We are floating lighter than air, unconstrained by ecological limits or even by truth itself (after all, denying truth is a luxury accessible only to those with a lot of surplus resources).

But will this persist indefinitely – or will it all come crashing down?

As Hanson correctly points out, the sum of human and Earth history hints that it will be the latter. Malthus will have his revenge. Renewed struggle for survival will scour away the degenerate and the superfluous relics of yesteryear, postmodernism will be declared heretical, and the new Caesars will Make Art Great Again!

Nice. Way to slip in a Trump plug at the end. I still need to get into the data on the Malthusian thing. How many hours did hunter gatherers need to work each day to survive again?

You clearly get the political aspect of art very well, yet you seem to skim over the “language of system 1” aspect. Certainly Basquiat digs into the subconscious in his work. Also notice that he’s drawing on the struggle of blacks in the new world. It’s sort of hard to argue that they are floating away from lack of burdens placed upon them. But I agree that not ALL art serves all these functions I outline. Even strange modern art populates system 1 with new patterns though.

Art is America’s soft power abroad. The world consumes our movies and our music. How successful is N.Korean media in the global market place?

A lot less than agriculturalists, to be sure. This doesn’t “disprove” Malthusian theory as you seem to constantly insist though. 😉 First off, the much greater variability of food production amongst HGs meant that they had to maintain a much larger safety margin for longterm population stability as opposed to grain-hoarding sedentary civilizations. Second, HG societies were two orders of magnitude more violent than advanced agriculturalists and an order of magnitude more violent than the early agriculturalists. The violence mechanism was consistently effective at keeping HGs within their ecological limits. A spear in your gut over a battle for a hunting ground is a Malthusian control just as starvation is!

***

I don’t really dispute anything in your comments in the last two paragraphs. My basic argument is that no longer subjection to selection for its effectiveness at increasing survival value, be it of the individual, the state, or some other institution such as the Church, modern art on average has become much less effective at that. And as a consequence, on average, it has moved away further from both truth and beauty.

Ironically, the locus of a lot of the great art that does exist today has shifted over to fantasy and sci-fi. Truth might be optional so far as the real world is concerned, but speculative fiction readers do demand some degree of verisimilitude in their fictive worlds!

Doesn’t the core of Malthusian theory suggest that a population will grow to consume all available resources? The idea of margins seems anti-malthusian. Violence also shouldn’t matter as long as more work could lead to greater collection of resources and thus greater populations. I don’t understand how hours of work doesn’t matter. What do YOU mean by Malthusian limits?

Congrats on your recent podcast with Robert Stark!

NO. No, no no.

What you describe here is called overshoot, and is typically followed by collapse.

Malthusianism basically implies that the population will merely grow until it hits the limits of the land’s carrying capacity. This is an equilibrium, in which most people have few or zero food surpluses (that is, a “subsistence” level of existence). This was historically the usual mode of human existence and economic historians can approximate it as an annual income of $400 Geary-Khamis dollars (1990).

It just so happens that this equilibrium did not tend to be very stable, because a series of shocks – e.g., a series of bad harvests caused by bad weather, a nomad invasion, etc. – could trigger a cascading collapse (i.e., the carrying capacity was reduced without an immediate commensurate fall in population, which automatically resulted in overshoot). This happened with remarkable regularity in China once every ~300 years from the Han to the Qing dynasties.

Paradoxically, violence is great under Malthusian conditions (assuming you prefer dying by sword rather than starvation). Due to high birth rates, the death rate also needs to be high. In nice civilized Malthusian societies, this takes the form of chronic malnutrition and disease made worse by overwork, and the occasional famine. In hyperviolent Malthusian societies, like amongst most hunter-gatherers, it comes more often in the form of chronic warfare.

OK, that’s interesting. I need to read up on this Malthus question more. I have in my notes to look up “A Farewell to Alms.” Was there a better reference for this?

If I accept this idea that population will increase until it has reached carrying capacity, but you don’t deny that this still allowed foraging humans a great deal of free time, then it’s not clear how you can make the assertion that art is a product of the dreamtime. The reason I keep harping on hours of work needed per day to subsist as a forager is to show that there is plenty of time for art in that environment. Presumably because doing more work cannot extract more food from a foraging area beyond a certain low threshold. I think it’s very hard to make the case that the earliest art was a product of dreamtime overabundance.

I think your conception of postmodernism is narrow-minded and confused. Consider that there can be diverse notions of beauty and there is likely no unified theory of aesthetics..

Pingback: Persistence in the Environment is the Meaning of Life - The Oakland FuturistThe Oakland Futurist